Burns Night

Burns Night

Who was Robert Burns?

Ask any Scot about Burns Night and their eyes will mist with tears and a

fierce pride will set fire to their blood. Whisky glasses chink and haggis start running for their lives

(but only round in circles).

But why? Who was Burns and why do Scots and friends of Scotland all over the world gather together to celebrate his life and works around the time of his birthday on 25th January?

Ask any Scot about Burns Night and their eyes will mist with tears and a

fierce pride will set fire to their blood. Whisky glasses chink and haggis start running for their lives

(but only round in circles).

But why? Who was Burns and why do Scots and friends of Scotland all over the world gather together to celebrate his life and works around the time of his birthday on 25th January?

The short answer is that Robert Burns was one of the finest poets that ever lived. A humble Scottish farmer who rose to become the delight of the Edinburgh elite yet never lost touch with the trials of the common man, he lived and died during some of the most turbulent times in Scottish history.

Songs and Poems

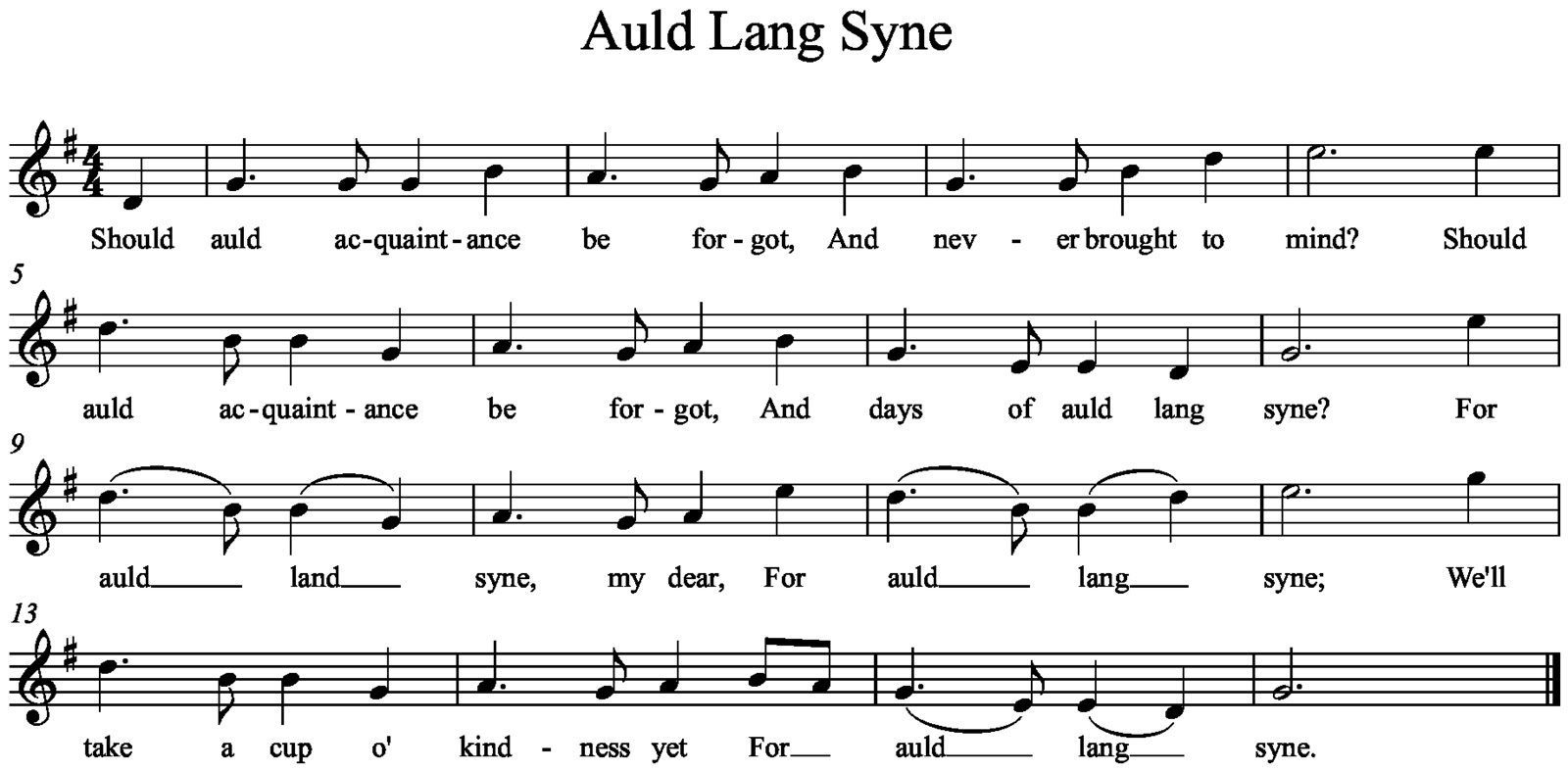

Burns was born on 25th January 1759, and died at only 37, but boy did he pack a lot in during those short few years. His poems and songs

are famous throughout the world, even if people often do not know that Burns was their author. Think Auld Lang Syne

, sung at precisely midnight

every New Year’s Eve, or the St Valentine's Day favourite My Love is Like a Red, Red Rose

.

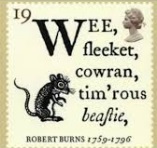

Burns' poems are equally memorable. Consider the compassion and empathy of

Burns' poems are equally memorable. Consider the compassion and empathy of To a Mouse

, the trembling beastie, its nest ruined by his plough, with the famous line

the best laid schemes o' mice an' men gang aft agley

, later to give John Steinbeck the title of his renowned novel. As the French poet Paul Verlaine said

The spirit of Burns dances in the lines of his poetry, where nature and emotion intertwine beautifully.

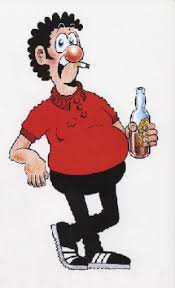

Or enjoy above all, the wit, vivid imagery and epic narrative of Burns’ supernatural masterpiece Tam o’Shanter

, the cautionary tale of an

Ayrshire farmer, to drink inclined, who left at last his favoured ale-house, only to find himself catch'd wi' warlocks in the mirk, by Alloway's auld haunted kirk

", but saved in the end by the breakneck speed of his faithful mare.

Burns Supper

A Burns Supper is a traditional Scottish celebration in honour of Burns’ life and works, combining traditional Scottish food (notably the world-renowned haggis), drink, poetry, music and dancing. The evening follows a typical, well-structured programme:

The meal begins with a recitation of the Selkirk Grace, a traditional Scotttish blessing, expressing gratitude for having food to eat, and compassion for those who do not.

Some hae meat and canna eat,

And some wad eat that want it; But we hae meat, and we can eat, Sae let the Lord be thankit

The Selkirk Grace- with translation

There then follows the ceremonial Piping In Of The Haggis. The haggis is carried in on a platter, typically held by the chef who prepared it,

led by a piper in full Highland regalia. Guests stand and applaud as it enters, honouring the haggis as the centerpiece of the meal.

The chef places the platter before the chairperson presiding the event, and is invited to drink a glass of of whisky (a dram

) for his efforts.

The first recitation of the evening then takes place - Burns' poem Address to the Haggis

, a humorous, dramatic, and affectionate hymn of praise to the haggis as a

hearty, honest, traditional Scottish dish. He celebrates this Great chieftain o' the puddin' race'

as the food of strong, hardworking people and contrasts it

with fancy, delicate dishes eaten by the wealthy. The poem is theatrical, filled with vivid imagery and comic exaggeration.

During recitations, the speaker usually gestures with a knife and dramatically cuts open the haggis at a key line.

Ye Pow’rs wha mak mankind your care,

And dish them out their bill o’ fare,

Auld Scotland wants nae skinking ware

That jaups in luggies;

But, if ye wish her gratefu’ prayer,

Gie her a Haggis!

Address to a Haggis- full text with translation

Following on from the fun of the Haggis comes the central speech of the evening, The Immortal Memory

, a formal tribute to

Burns' life, work and enduring legacy. A typical Immortal Memory covers Burns' life, his upbringing, work, struggles, romantic adventures and literary career, as well as

his values and relevance today - his compassion for the poor, political radicalism, celebration of ordinary people belief in equality, love of nature and international influence. In Luxembourg, on alternate years

we feature a local speaker, and then typically a speaker from Scotland. Some famous names have appeared in the forty-odd years of the Burns Supper.

What though on hamely fare we dine,

Wear hoddin grey, an’ a that;

Gie fools their silks, and knaves their wine;

A Man’s a Man for a’ that:

For a’ that, and a’ that,

Their tinsel show, an’ a’ that;

The honest man, tho’ e’er sae poor,

Is king o’ men for a’ that.

Is There For Honest Poverty- full text with translation

There then follows the

There then follows the Address to the Lassies

, in which a man dares to make a speech to the women present (the lassies

). The

speech is typically a playful, affectionate toast mixing humour, teasing, praise for women's strengths, wit and influence, and often

references to Burns' well known admiration for women. It concludes with the toast To the Lassies!

.

Of course the evening would not be complete

without the lassies' reply, and in return one of their number delivers a heartfelt response in kind, teasing, rebutting the jokes made in the Address, and celebrating the strengths and contributions of women. The Reply from the Lassies concludes with the inevitable toast

Of course the evening would not be complete

without the lassies' reply, and in return one of their number delivers a heartfelt response in kind, teasing, rebutting the jokes made in the Address, and celebrating the strengths and contributions of women. The Reply from the Lassies concludes with the inevitable toast To the Laddies!

.

If the Reply from the Lassies

concludes the standard programme, it rarely marks the end of the evening.

Typically in Luxembourg we sing Scots, Wha Hae

, one of Scotland's several unofficial national anthems, an emotional, defiant and

patriotic song celebrating freedom, resistance and national pride, and Burns' indirect comment on freedom and oppression in his own time,

notably in relation to the French Revolution.

Lay the proud usurpers low! Tyrants fall in every foe! Liberty's in every blow! Let us do or dee!

Scots, Wha Hae- full text with translation

Further

recitations may be performed from the Bard's great body of work, often the immortal, cinematic Tam o'Shanter

,

the witty To a Louse

,

in which the sight of a louse on a lady's bonnet in church causes the poet to refelct on vamity and persepctive, the biting satire on

hypocrisy

Holy Willie's Prayer

,

or the nostalgic portrait of family life in The Cotter's Saturday Night

.

And last but not least, what we call in Luxembourg Sangs and Clatter

, a ceilidh of music and dancing continuing into the small hours.